8 Must-Know CV Tips for Radiologists—Whether Job Hunting or Not

If your Curriculum Vitae isn’t all it could be, you may as well be stacking trophies in a cave. I say this as a longtime radiologist recruiter who...

Remote radiologist jobs with flexible schedules, equitable pay, and the most advanced reading platform. Discover teleradiology at vRad.

Radiologist well-being matters. Explore how vRad takes action to prevent burnout with expert-led, confidential support through our partnership with VITAL WorkLife. Helping radiologists thrive.

Visit the vRad Blog for radiologist experiences at vRad, career resources, and more.

vRad provides radiology residents and fellows free radiology education resources for ABR boards, noon lectures, and CME.

Teleradiology services leader since 2001. See how vRad AI is helping deliver faster, higher-quality care for 50,000+ critical patients each year.

Subspecialist care for the women in your community. 48-hour screenings. 1-hour diagnostics. Comprehensive compliance and inspection support.

vRad’s stroke protocol auto-assigns stroke cases to the top of all available radiologists’ worklists, with requirements to be read next.

vRad’s unique teleradiology workflow for trauma studies delivers consistently fast turnaround times—even during periods of high volume.

vRad’s Operations Center is the central hub that ensures imaging studies and communications are handled efficiently and swiftly.

vRad is delivering faster radiology turnaround times for 40,000+ critical patients annually, using four unique strategies, including AI.

.jpg?width=1024&height=576&name=vRad-High-Quality-Patient-Care-1024x576%20(1).jpg)

vRad is developing and using AI to improve radiology quality assurance and reduce medical malpractice risk.

Now you can power your practice with the same fully integrated technology and support ecosystem we use. The vRad Platform.

Since developing and launching our first model in 2015, vRad has been at the forefront of AI in radiology.

Since 2010, vRad Radiology Education has provided high-quality radiology CME. Open to all radiologists, these 15-minute online modules are a convenient way to stay up to date on practical radiology topics.

Join vRad’s annual spring CME conference featuring top speakers and practical radiology topics.

vRad provides radiology residents and fellows free radiology education resources for ABR boards, noon lectures, and CME.

Academically oriented radiologists love practicing at vRad too. Check out the research published by vRad radiologists and team members.

Learn how vRad revolutionized radiology and has been at the forefront of innovation since 2001.

%20(2).jpg?width=1008&height=755&name=Copy%20of%20Mega%20Nav%20Images%202025%20(1008%20x%20755%20px)%20(2).jpg)

Visit the vRad blog for radiologist experiences at vRad, career resources, and more.

Explore our practice’s reading platform, breast imaging program, AI, and more. Plus, hear from vRad radiologists about what it’s like to practice at vRad.

Ready to be part of something meaningful? Explore team member careers at vRad.

6 min read

Benjamin W. Strong, MD

:

July 13, 2023

Benjamin W. Strong, MD

:

July 13, 2023

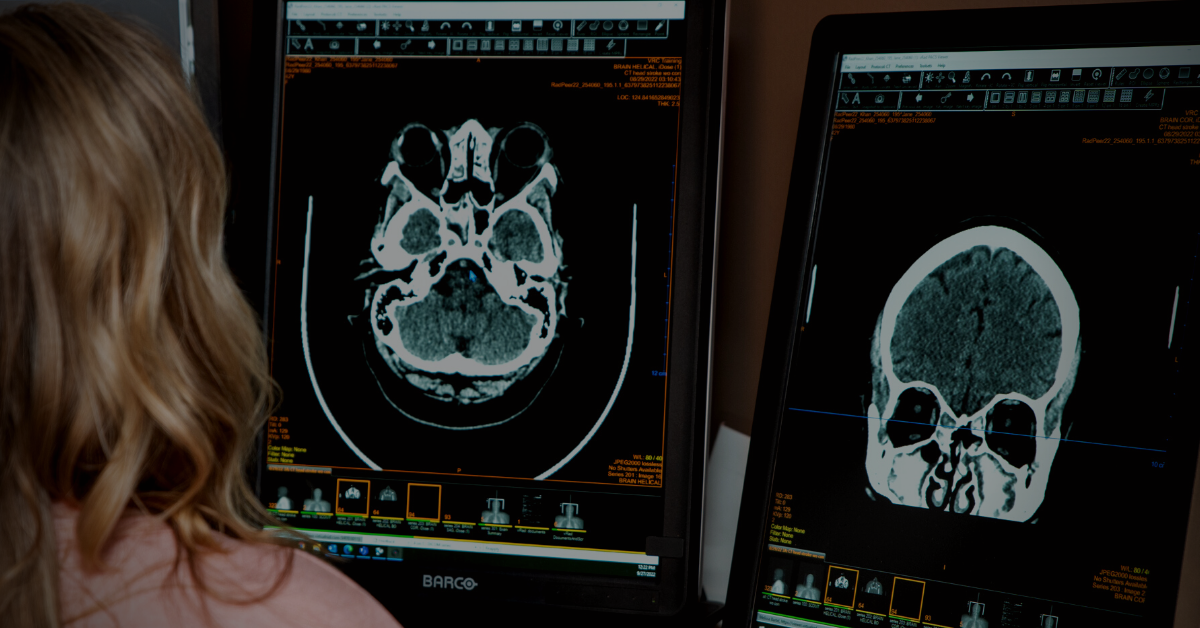

The thought of missing a critical finding can strike fear in the heart of even the most seasoned radiologist. So, when I’m asked which findings are most commonly missed, I don’t hesitate to answer. The most-missed findings that can lead to a devastating patient care outcome, or are most likely to land you in court, are spinal epidural abscesses, aortic dissection, ischemic bowel, intracranial hemorrhage and pulmonary embolism. The first three are most likely to result in a malpractice claim and may account for 40% of all indemnity payments paid by a practice. The remaining two, while they might not end in a lawsuit, are still some of the most common critical misses.

The second thing radiologists want to know is, “What can I do to reduce the possibility of missing one of these pathologies?” And my answer is: Develop a solid search pattern and stick to it. With every single read.

In my roughly 10 years on the vRad QA committee, I noticed that certain pathologies seemed a lot more likely to be missed and certain actions — or lack of them — more likely to end with an incomplete or incorrect diagnosis. But these were only anecdotal conclusions. I needed data to quantify my informal observations so we could prioritize our AI development program for QA and build the most important models first.

So, I embarked on a thorough analysis of every legal claim made against vRad radiologists in the period between June 2017 and October 2020. During that time, we read almost 20 million studies and had 220 malpractice claims, which equates to about 137 years’ worth of experience for an average-sized practice. In the end, I identified 45 cases that resulted in a payout, costing tens of millions of dollars over the space of those 41 months.

Keep in mind, during that period our 500 radiologists read nearly 20 million studies and logged an error rate of just 1.3 major misses per 1,000 reads—one-third the rate of the oft-cited Wilson Wong study on QA.

In my analysis, I included every piece of information I could about each one — what type of miss was alleged, what type of study was involved, whether the standard of care was met, if there was a failure of communication involved, etc. I also looked at the financial aspect of each claim. I read the depositions. I read the reports of counsel. I analyzed every aspect of these cases.

Some of the information that emerged was surprising. For instance, it wasn’t the radiologists with above-average miss rates who were being sued. Nor was it the hyper-productive ones, where you might conclude that they were in too much of a hurry and missed something because of that. In fact, two-thirds of the radiologists involved in suits were below both our average productivity rate and our average miss rate. The odds of being part of a malpractice suit seemed to be totally random.

Another surprising conclusion was about what lay at the heart of most med mal cases. I went into my analysis thinking poor communication or lack of communication would be the common denominator in at least one-third and maybe even half the cases. Instead, fewer than 12 percent came down to communication issues.

What appeared from the data were 7 things radiologists can do to avoid claims of medical malpractice. The one that topped the list didn’t surprise me at all. The failure to adhere to an established search pattern was a key factor in every malpractice case I analyzed involving a diagnostic error.

You can read about all 7 in my previous article, but this story takes a deeper dive into why your search patterns are so important and some tips on how to incorporate them into your routine.

Let’s say you open a study on your worklist and immediately see an appendix that is five times its normal size. It’s swollen, turgid, enhancing, with stranding all around it — it’s the most obvious case of appendicitis you’ve ever seen. It might be tempting to only give cursory attention to other areas or even to skip everything that comes before the appendix in your search pattern. Herein lies the pitfall. You risk missing another finding which is potentially just as important as the appendicitis.

Search patterns are effective in that they divide the radiology interpretation process into two phases: the findings phase, identifying all the abnormalities in a given examination; and the cognitive integration phase, where you take stock of your findings and put it all together to determine a diagnosis. These are really two distinct exercises that call for different modes of thinking. Muddling them together can leave you open to misses that might not happen otherwise.

Keep the two phases separate. First, follow your search pattern through the organs and structures, without trying to interpret what you see. Only then, when you’ve exhausted your search pattern and noted everything, not just the obvious, is it time to shift mental gears and begin to interpret your findings.

If the concept of search patterns is new to you and you need a blueprint to start from, the best thing to do is to download recommended templates and use the structured reporting categories as your basic blueprint — but don’t think that a search pattern begins and ends with this simple list of organs and structures. It’s a starting point, a macro-list, within which you must develop your own micro-list of search pattern points.

Each category should trigger within your mind a subset of additional search pattern points that you can then work your way through. It takes practice. It takes repetition. It must become a habit — it must become automatic, so that when you see “category X” you automatically begin ticking off point A, point B, point C, etc.

Your search pattern will evolve over the course of your training and practice. You’ll adapt it based on many factors, such as things that you find are common, things that you know you’ve missed in the past, and how your brain works in moving from one point to the next. Everybody does it slightly differently, but ultimately those who implement the search pattern approach all end up in the same place.

This may be an unpopular opinion, but I believe dictating into a template is a terrible habit. Here’s why:

The fundamental goal of all radiology workflows should be to ensure that the radiologist’s eyes — and brain — are always focused on the diagnostic images. Dictating into templates distracts from this. Many popular dictation programs present the radiologist with a template containing different fields they can dictate into. The rad advances through fields with the press of a button or a voice command but must constantly reference the template throughout the course of the interpretation. Their attention bounces back and forth between the diagnostic images and the reporting screen like a tennis fan at a match rather than staying focused on the images.

Not only is this a distraction; the software template almost certainly won’t sync with the search pattern you’ve developed for that procedure. The template is beyond unhelpful and can be destructive and dangerous. A search pattern incorporates many factors, including knowledge of one’s own blind spots and flaws that need to be mitigated. Forcing a new search pattern onto a radiologist throws this out the window. Organic changes in your pattern are natural and desirable, but being forced by a template to conform to an alien pattern is asking for trouble.

Software that conforms to your search pattern rather than asking you to change your pattern to fit exists. It is what we use at vRad.

When a radiologist opens a study on our reading platform, they’re presented with a reporting page in which all of the information on that study, such as procedure name, patient information, billable clinical history, and study information is automatically imported, but the findings area is completely blank. This lets the radiologist keep their eyes on the images, adhere to their own personal search pattern, and dictate according to that, point by point. When they’ve finished, they simply click a button to sign and process the report.

Using natural language processing (NLP), the software parses every sentence the radiologist has uttered to determine what organ or structure is being described. It then takes those sentences and categorizes them into the finalized, structured report.

If you have a dictation system that allows you to document your progress through your search pattern, drop in a line of dictation for each step or organ you've evaluated. This way, if you're interrupted, you’ll have confidence in your system to look at your in-process dictation, determine where you were, and pick up at the next step of your search pattern.

While vRad’s software is the most mature and robust, other vendors are beginning to add this type of NLP-based reportage as an option, and this is something to look for in whatever software you’re using.

Despite the obvious benefits of developing and using a regimented search pattern, a surprising number of radiologists are still resistant to the idea. Why? I’m not sure. Some may see it as a direct commentary on their competence. Or they may feel that their current software does a perfectly adequate job of segmenting the read into a pattern. Or it may be a holdover from the days when radiology was simpler, X-rays were the standard, and even ultrasound was an emerging technology.

But technology has evolved at an exponential rate in the past few decades, and imaging has become so complex that the old ways of doing things simply aren’t enough anymore. It's entirely possible to miss a tumor the size of a grapefruit if you’re not looking at it in the right window setting, scrolling at the right speed, and in the right frame of mind. You can also miss tiny, subtle things that may only appear in one image out of a set of hundreds. There has been a logarithmic jump in the information available, and it’s an absolute necessity that you approach this much more complex task in an ordered, methodical, regimented fashion.

You need a search pattern.

Using a search pattern is perhaps the number one thing you can do to avoid a malpractice claim. I don’t think it’s sufficiently emphasized in the world of radiology, either in training or in life afterward, but the evidence is clear: adherence correlates to better accuracy. Establish a methodical, regimented search pattern for every procedure. Know precisely what you’re going to look at, and what you’re going to look for with every organ.

Back to Blog

If your Curriculum Vitae isn’t all it could be, you may as well be stacking trophies in a cave. I say this as a longtime radiologist recruiter who...

1 min read

One of the first questions any radiologist has when exploring a new opportunity is about salary. It's an important question. At vRad, some...

.png)

I’ll be honest, I had no plans to go into teleradiology straight from residency. However, I fell into it because economic conditions meant choices...

vRad (Virtual Radiologic) is a national radiology practice combining clinical excellence with cutting-edge technology development. Each year, we bring exceptional radiology care to millions of patients and empower healthcare providers with technology-driven solutions.

Non-Clinical Inquiries (Total Free):

800.737.0610

Outside U.S.:

011.1.952.595.1111

3600 Minnesota Drive, Suite 800

Edina, MN 55435