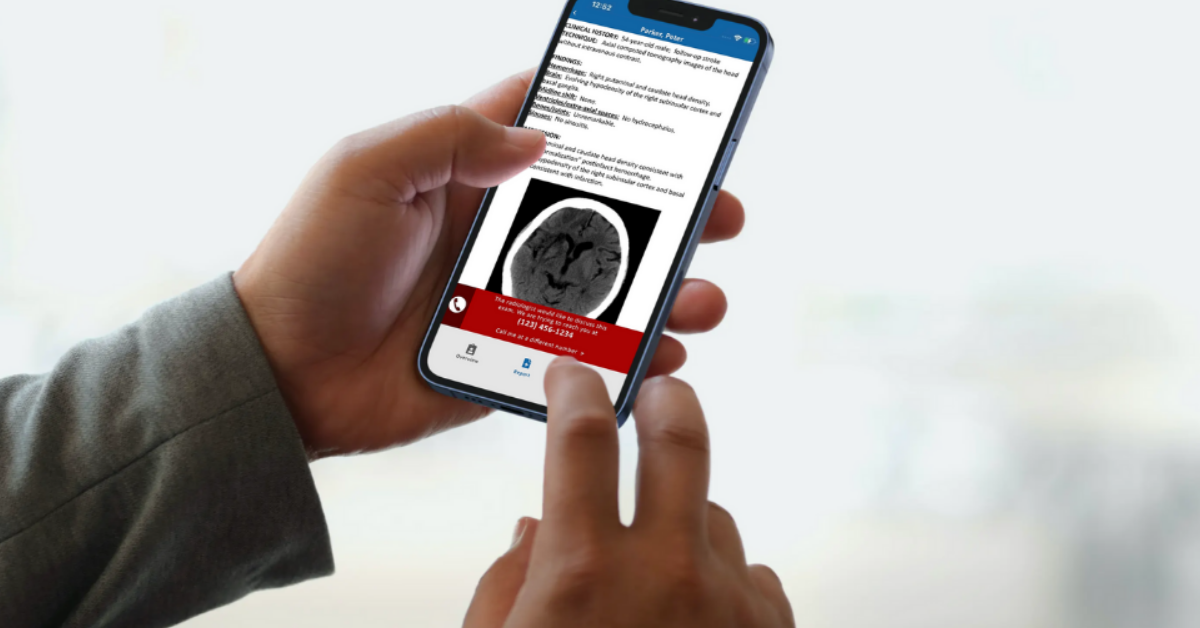

Rad Results: The Mobile App That Connects Radiologists with the Patient Care Team

Originally published by Michael Walter on Radiology Business In radiology, it is vital for radiologists to connect with the entire patient care team...

Remote radiologist jobs with flexible schedules, equitable pay, and the most advanced reading platform. Discover teleradiology at vRad.

Radiologist well-being matters. Explore how vRad takes action to prevent burnout with expert-led, confidential support through our partnership with VITAL WorkLife. Helping radiologists thrive.

Visit the vRad Blog for radiologist experiences at vRad, career resources, and more.

vRad provides radiology residents and fellows free radiology education resources for ABR boards, noon lectures, and CME.

Teleradiology services leader since 2001. See how vRad AI is helping deliver faster, higher-quality care for 50,000+ critical patients each year.

Subspecialist care for the women in your community. 48-hour screenings. 1-hour diagnostics. Comprehensive compliance and inspection support.

vRad’s stroke protocol auto-assigns stroke cases to the top of all available radiologists’ worklists, with requirements to be read next.

vRad’s unique teleradiology workflow for trauma studies delivers consistently fast turnaround times—even during periods of high volume.

vRad’s Operations Center is the central hub that ensures imaging studies and communications are handled efficiently and swiftly.

vRad is delivering faster radiology turnaround times for 40,000+ critical patients annually, using four unique strategies, including AI.

.jpg?width=1024&height=576&name=vRad-High-Quality-Patient-Care-1024x576%20(1).jpg)

vRad is developing and using AI to improve radiology quality assurance and reduce medical malpractice risk.

Now you can power your practice with the same fully integrated technology and support ecosystem we use. The vRad Platform.

Since developing and launching our first model in 2015, vRad has been at the forefront of AI in radiology.

Since 2010, vRad Radiology Education has provided high-quality radiology CME. Open to all radiologists, these 15-minute online modules are a convenient way to stay up to date on practical radiology topics.

Join vRad’s annual spring CME conference featuring top speakers and practical radiology topics.

vRad provides radiology residents and fellows free radiology education resources for ABR boards, noon lectures, and CME.

Academically oriented radiologists love practicing at vRad too. Check out the research published by vRad radiologists and team members.

Learn how vRad revolutionized radiology and has been at the forefront of innovation since 2001.

%20(2).jpg?width=1008&height=755&name=Copy%20of%20Mega%20Nav%20Images%202025%20(1008%20x%20755%20px)%20(2).jpg)

Visit the vRad blog for radiologist experiences at vRad, career resources, and more.

Explore our practice’s reading platform, breast imaging program, AI, and more. Plus, hear from vRad radiologists about what it’s like to practice at vRad.

Ready to be part of something meaningful? Explore team member careers at vRad.

4 min read

Benjamin W. Strong, MD

:

November 2, 2021

Benjamin W. Strong, MD

:

November 2, 2021

.png)

Originally published by Michael Walter on Radiology Business

Medical malpractice claims are a significant source of anxiety for all radiologists. Unfortunately, decisions made in the heat of the moment, with the absolute best intentions, can still land a specialist in court.

In my role as chief medical officer for vRad, I’m intimately involved with our radiology malpractice claims and have observed commonalities among them. To quantify these observations, I recently analyzed all 220 claims made against vRad radiologists between June 2017 and October 2020—applying a detailed classification taxonomy including the alleged type of miss, study type, if the standard of care was met, if communication failures contributed, settlement, and so on.

What emerged from that data was a clear set of guidelines to help radiologists avoid the costliest and most likely cases to go to trial.

Keep in mind, during that timeframe, our 500+ radiologists read nearly 20 million studies and logged an error rate of just 1.3 major misses per 1,000 reads—one-third the rate of the oft-cited Wilson Wong study on QA.

I analyzed vRad’s claims in great detail and formed the following prioritized recommendations for avoiding medical malpractice in radiology.

When I first started this research, I guessed that communication issues were behind one-third or even one-half of all medical malpractice cases rather than an actual missed finding. But, to my surprise, communication issues were only a factor in fewer than 12% of the cases.

We tend to see this issue pop up with acute pneumonia, which does not seem to set off the same alarm bells in a radiologist’s head as, say, an acute stroke would. But those simply must be called to the referring clinician—it is not enough to simply put it into the written report.

New diagnoses of pneumonia in an acute care setting should always result in a phone call. Failure to treat pneumonia quickly can and does result in sepsis and severe morbidity and mortality.

Around 35% of the reports issued by our radiologists are preliminaries. These are typically reviewed the next day by our client radiologists onsite before they issue a final report.

Both remote and onsite radiologists can get tangled up in legal issues with preliminary reads.

For the remote radiologist, there can be a temptation to think, “If I miss something, the next person will catch it.” The same can be said for the second reader. They may not give the study their full effort since another radiologist has already read it.

In reality, this imagined “safety net” is just not there.

Looking at the data, in preliminary studies progressing to lawsuits, approximately half of the missed findings by the initial remote radiologist were also missed by the second onsite radiologist. And the other half, where the second radiologist saw the finding, that radiologist put it in the final report but failed to call anyone about it.

Both radiologists will end up in court in these instances as preliminary status is not a defense for a missed finding, whether emergent or not.

Many practice policies and quality initiatives focus on giving radiologists plenty of background data, whether it’s prior studies, good clinical history, lab values, and so on.

What we have seen, however, is that these things were not major contributors in a single medical malpractice case. Much more important is getting access to and viewing all of the planes of imaging—meaning the axial, coronal and sagittal—and using them routinely in every study evaluation.

A lengthy report with multiple, seemingly disparate findings and no unifying diagnosis can be an indicator to the reading radiologist that greater cognitive effort is required for that particular study.

I’ve seen this most often in ischemic bowel cases, where multiple nonspecific findings such as dilated bowel loops or peritoneal fluid can be present, but the specific cause (vascular compromise) remains invisible or elusive. In these cases, it is tempting to leave things at a list of findings that are not a diagnosis and do little to help direct a clinician’s efforts. Instead, reports that amount to “notes but no music” should prompt the radiologist to return to the case in search of that unifying diagnosis.

With contrast-enhanced MRI studies, it is essential to take a specific, cognitive note of which image sequence you are looking at to avoid what I refer to as the total reversal phenomenon—an abnormal finding so extensive that it looks normal.

I see this in extensive meningeal/epidural infections and in diffuse bone marrow replacement. Extensive enhancement in meningitis can cause the gadolinium sequences of a spine or brain to look much like a normal T2 sequence, and diffuse marrow infiltration can make an abnormal T1 look like a normal T2. Taking a mental note of the exact sequence parameters you are viewing is the best strategy to avoid this issue.

Cases of missed aortic dissection that end up in court often share a few traits that explain why the radiologist didn’t see the critical finding. For example, one scenario involves studies ordered for something other than aortic dissection, making it very difficult to visualize the aorta. An abdomen study, for example, will only include the abdominal portion of the aorta in the image set. Likewise, a chest CTA done for pulmonary embolism will have intravenous contrast in an entirely different vessel than the aorta. Or, for that matter, calling an aortic dissection on a study without any contrast at all is exceptionally difficult. But it can be done.

The second common thread is an absence of clinical history to suggest aortic pathology. None of the aortic dissection malpractice cases I’ve reviewed mentioned the classic description of tearing pain between the chest and back. Instead, there were histories of flank pain common with renal stones, pain during inhalation suggesting possible pulmonary embolism, or any number of referred pains (such as neck) that can be misleading to the radiologist.

Always assess the aorta to the best of your ability, no matter the imaging parameters or reason for the exam.

That brings us to the number one thing you can do to avoid a medical malpractice suit.

Even before this recent analysis, going back to the decade I spent on our Quality Assurance Committee, I can tell you the vast majority—in fact, nearly all missed findings—are the result of failing to adhere to an established search pattern for that specific procedure.

Every radiologist should develop and follow a strict, organ-by-organ checklist for every interpretation. Know precisely what you’re going to look for, look at, and comment on.

I’ve got to look at the spinal canal. I’ve got to look at the aorta. I’ve got to look at the superior mesenteric artery. That’s a big one, by the way—the most missed single entity in all the cases I reviewed.

Adhering to your search pattern is the only way, in my opinion, to avoid those errors that the next morning are so obvious, so visually conspicuous and so avoidable.

Back to Blog

Originally published by Michael Walter on Radiology Business In radiology, it is vital for radiologists to connect with the entire patient care team...

.png)

At some point in your career, if you are lucky, you find somebody approachable who’s blazed trails and navigated difficulties in ways you can model....

I love to watch the colors change in October, when pink is in full display during Breast Cancer Awareness month. With each hot-pink scarf, T-shirt...

vRad (Virtual Radiologic) is a national radiology practice combining clinical excellence with cutting-edge technology development. Each year, we bring exceptional radiology care to millions of patients and empower healthcare providers with technology-driven solutions.

Non-Clinical Inquiries (Total Free):

800.737.0610

Outside U.S.:

011.1.952.595.1111

3600 Minnesota Drive, Suite 800

Edina, MN 55435